1. From observation to measurement: Birth of skin biometrology. The skin is the visible organ par excellence. Taking care of your skin is an integral part of life. Whatever civilizations, humans have always sought to embellish their image. Egyptian papyrus already described the first beauty recipes. In the 16th century, Latin writings were devoted to cosmetology. The first of its kind is that of Girolamo Mercuriale, De decoriatione Liber, published in 1585. It is only much later, with the first hygiene precepts, that the study of the skin will interest some scientists.

The first classification of skin goes back to Auguste Debay, doctor, in a work of medical hygiene¹ of the face and the skin, of 1850, revisited in 1879.

The first descriptions

According to A. Debay,"the human envelope, the skin (…) differs, however, in a very distinct way, according to races, climates, temperaments, professions, sexes, age, etc.". He will thus distinguish skins into two categories: oily or dry, then white like"thin and almost stretched skins of Parisian or Londonian women", as opposed to"tanned skins of peasants or sunburned Bedouin". He will push his observation by describing more precisely the characteristics of each: - Oily skin with abundant cell tissue, a lot of secretions and excretions that he describes as"wet temperament" skin, - dry skin, with a rarer, less rich cellular tissue, with less secretions, found in"dry, bilious and nervous temperaments".

As for the colour, for which he observes many nuances, it is purely of genetic origin and classified into only two categories: white or black. Asian skins are not yet reported.

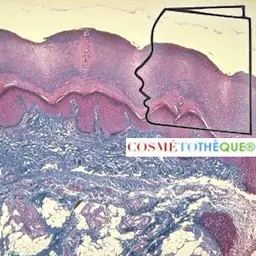

Others, like Dr. M. Baron² will be interested in skin diseases, by delivering an anatomical description of it. Thanks to the observation under microscope, he will describe it as being composed of four elements which are: the epidermis, the papillary, nervous and vascular tissue, the mucous layer and the dermis.

This description results from the observation at different stages of skin diseases and/or deformities of skin tissue such as corns, calluses and'other horny productions' for the epidermis.

Each of its categories will be detailed after dissection, with mention of chromatogenic (color), trikogenic (causing"diseases" such as alopecia, baldness, lichen…), sebaceous (acne, impetigo, lupus…) and sweaty (morbid sweats, military eruptions, sudamina…). The symptoms of the disease were, at that time, at the origin of the description.

More slightly, comments on the difference between the skin of blonde and brunette women leave one perplexed. Thus, blondes would generally have whiter, rosier and finer skin, while brunettes would have softer skin to the touch because of a finer grain and free of freckles. This brown skin would be less radiant but less fragile to superficial skin affections (dartres) and would age better… A beautiful skin would be supple, polished, fresh, transparent, slightly pinkish.

The author shows a preference for the skins of blond women, which he describes as"more feminine". And to add some with an almost idyllic description:"when to a long blond hair, it unites the perfection of the features and the forms, it is the Venus Anadyomenus coming out of the breast of the wave". No comment!

He will continue by addressing the concept of skin beauty and give a first definition of cosmetics.

Beauty and cosmetics

The Greek origin of the word cosmetic means"to embellish". Thus, cosmetics is the art of cultivating, developing and preserving the beauty of the body, but also of fighting against defects and other imperfections. He dares to sum up this art by"covering ugliness with an attractive mask".

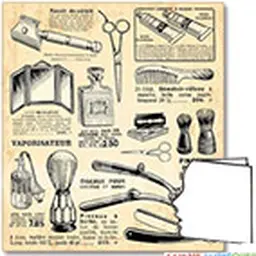

It briefly defines three main classes of cosmetic products: - products that have not undergone any chemical transformation. This category includes thermal waters, floral waters (distilled waters of rose, orange tree, plantain…), milk… Hebrew oils and fats, liqueurs, pastes ; - first-class cosmetics that have undergone chemical transformations (emulsions, macerations, decoctions, ointments with salts, resins or active ingredients) recommended for second youth; - medical cosmetics, the responsibility of the pharmacist, generally substances presenting a danger, with curative virtues. Finally classified in drugs, they will not be described in cosmetic books.

Later, in 1913, Dr Paul Gastou³, head of the central laboratory at Saint-Louis Hospital in Paris, classified cosmetics into three categories in his cosmetic and aesthetic form: - household cosmetics, empirical recipes whose use has confirmed their effects, - Pharmacist cosmetics, which he recommends for use because prepared with precise know-how and utensils even if they are the most expensive; - perfumery cosmetics, made by master perfumers, but whose exact composition is not always known.

Under the heading"Beauty products", this classification has expanded somewhat as the pharmacy has found its own way. Remain OTC or QD (for"quasi drug"), a category apart for Japan and the United States, which could become widespread in the near future in view of the ever greater effectiveness of cosmetics. It is precisely thanks to this performance research that pharmacy, cosmetology and dermatology together will contribute to the knowledge of healthy skin.

The experimental approach to skin knowledge

The Saint-Louis Hospital in Paris and its dermatology school will contribute to the development of skin exploration techniques. At the very beginning, under the impetus of Jean Louis Alibert⁴, a doctor in Saint-Louis, an illustrated manual of 53 engravings of skin and head diseases was published in 1833. A work that will become a reference. Later, the advent of photography proved to be the ideal way to publish dermatology booklets as close to reality as possible and less expensive than drawings and engravings.

At the end of the 19th century, Professor Richerand attempted the first experiments on cutaneous absorption. It will thus show that the various elements contained in an aqueous bath can pass through the skin. He fed patients who could not feed themselves by wrapping them in cloths soaked in meat broth. Or, he observed that a bath composed of purgative substances produces the same effect as an oral administration, etc.. The precursor of the patch was born!

Research will then slowly evolve; links are forged between hospitals and universities. But it was really after the war that major research themes were set up.

In 1954, during the detergency congress, the French Society of Cosmetics asked Prof. Schneider, head of the dermatology clinic in Augsburg, about skin classification, apart from pathological skins. This one estimates that there are a multitude of different skins, whereas the cosmetologists of the time see essentially two types of skins: that of the men with oily, seborrheic and wettable skin, and the dry skin.

For many years, skin types have been described primarily through aesthetic criteria to assist in the sale of products. It was Helena Rubinstein who, in 1910, proposed the first classification into three skin types Dry, greasy and normal.

However, the measurement of water and fat content could help to qualify this binary categorization. As well as the relationship between its variations, physiological behaviour and the clinical appearance of skins. During this exchange, Prof. Schneider reveals one of his methods for measuring skin penetration. The idea was to study the effect of a protective cream. Some time after application to the skin, it removes the excess with a cotton wool pad or by washing and immediately carries out patch tests with an irritating dose of turpentine to check the protective effect of the cream. The tests will show that the penetration was sufficient since the irritation tests were negative. Another method would have been to use radioactive isotopes.

Research activity on the skin really became dynamic in the 1980s, with the birth of cutaneous biology. This period corresponds to the setting up of Inserm research units such as that on cutaneous immunity in Lyon, on reconstructed epidermis in Paris and Lyon, on photo-dermatology in Nice and cutaneous biometrology in Besançon.

Another classification method will appear at about the same time, crossing observations from biometrology. This is the phototype classification according to Fitzpatrick revising to the color of peau⁶.

This topic will be discussed in our next chapter.

¹ Form of beauty, indicating the rational means to preserve the radiance of the complexion and the freshness of the skin; to dissipate rednesses, pimples, spots, ephelides, dartres and other cutaneous alterations; to prevent and straighten the deformities of the features of the face, Paris: E. Dentu, 1879. Extract from the book by E. Dentu, 1879, Hygiène médicale du visage et de la peau BIU Santé, Paris. Gastou Paul Louis, Face hygiene - Cosmetic and aesthetic form, 1913, BIU Santé Paris. ⁴Jean Louis Alibert, Traité complet des maladies de la peau, Cormon et Blanc, 1833, BIU Santé Paris.

|

Michelle graduated from ENSAM Montpellier (today SupAgro) in food sciences and started her career as a quality engineer in the Intermarché group. In 1993, fate led her to a more glamorous universe, that of cosmetics. She joined Chanel in Neuilly sur Seine. In 2008, change of direction for the professional press as editorial director. At the same time, at the end of 2012, she created her consulting firm to assist companies in the development of evaluation methods, cosmetics and scientific content writing. Finally, she is a teacher at ISIPCA on sustainable development modules, CSR, and the natural sector. She has collaborated with the Cosmetotheque® since its creation. |

This contribution was made by Michelle Vincent.

This contribution was made by Michelle Vincent.